Today’s rocky markets make for a market timing ses-pool. So what better time to offer a brief market timing 101 session,  AKA “How to explain a market timing update to your kids?”

AKA “How to explain a market timing update to your kids?”

I actually tested this on my 9 and 10 year old girls today. And here’s how it went.

Have you ever made a mistake or do something wrong in life that you were sorry about?

Answer: “Uhhh, yeesss,” long and drawn out with a quizacle look on their faces (….followed by “are we in trouble, Mom?”).

Then I asked, did you mean to make the mistake, or purposely do something wrong? And here, the answers were mixed.

The responses I got were “sometimes,” and one with a head down offered a shameful “yes,” and then I received a philosophical lecturing from my 9 year old how the origin of a mistake is rooted in not knowing you’re making a mistake or doing something wrong, unintentionally, in other words.

Wow.

So I framed the discussion to my kids based on making a mistake – simply because most statistics will point to market timing being just that, a mistake.

Here me out…

Most times, investors or advisors get a portion of the transaction correct, say, selling early before a correction – which feels great, by the way, BUT – it’s the not re-entering the market in a timely fashion, which can be the “mistake” in this instance.

Human nature would provide in this scenario that the great feelings of selling properly will always overshadow those, not-fully-invested-feelings of not getting back in, in time (ahem, investors nor advisors will rarely look at the opportunity cost of not re-investing “on time,” again, given the ever-lasting euphoria that accompanies avoiding significant losses correctly).

You don’t have to believe me:

Dalbar’s Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB) has been measuring the shortfall in retail investor real returns for 20 years.

“…when looking at long-term returns, the average asset allocation investor has underperformed both equity and fixed income indices. For the 5, 10 and 20-year timeframes, the average asset allocation investor failed to keep up with inflation.”

Investor bad behavior accounts for staggering investment underperformance. Translated for my kids: When investors tried to decide when it was best to buy or sell their investments – even when they got it 75% right (2013) – which is quite rare, they still made a mistake (underperformed the market).

“Despite “guessing right” 75% of the time, the average investor still trailed the broad equity market by 6.87%,” according to the 2013 DALBAR Study.

This is a mistake, yes?

My kids: “Well it’s only a half mistake – they got 75% of it right.”

I decided to not qualify that.

All of the “mistake” discussion was followed by sharing with the girls an enlightening article I read that touched on intentional and unintentional market timing, written by Rick Ferri, a contributor at Forbes.

Ferri shares many things that my kids understood, but what resonated most was the idea that sometimes you make mistakes that you didn’t mean to – AKA the “Unintentional Timer” (typically the emotion individual investor), and sometimes you make mistakes on purpose – AKA the “Intentional Timer” (typically, advisors using far-flung macro-economic or technical indicators to, as Ferri puts it, make them feel smart and justify their excessive fees).

Ah-ha.

What struck me most and made me want to relay all of this to my kids (since I’m such a market geek, rearing them this way at 9 and 10 years old) is something else Ferri offered:

“Being wrong on both (front and back end of a timing transaction) can lead to long-lasting detrimental effects. Capitulation in a bear market and then sitting out during the recovery creates deep psychosocial damage. This damage can keep investors away from the markets for an extended period of time – sometimes for life….Unintentional market timing wrongs can cut so deep that they may extend to the next generation. Children hear their parents complain about the stock market being rigged and how they will never invest in corporate America again. Remember Occupy Wall Street? This could be why many investors in their 20s are avoiding stocks altogether.”

I loved Ferri’s Intentional Vs. Unintentional philosophy – and my kids got it. “Both types of mistakes are bad,” my 10 year old offered. Followed by “We all learn from mistakes so that we make better choices later.”

Of course, my kids wanted to understand how mistakes in the market translated to their allowance possibly disappearing (versus growing) as this directly related to purchasing the next generation iPod touch. So, naturally they wanted to “see” just how costly these mistakes could be.

The best illustration I found came from this Schwab excerpt:

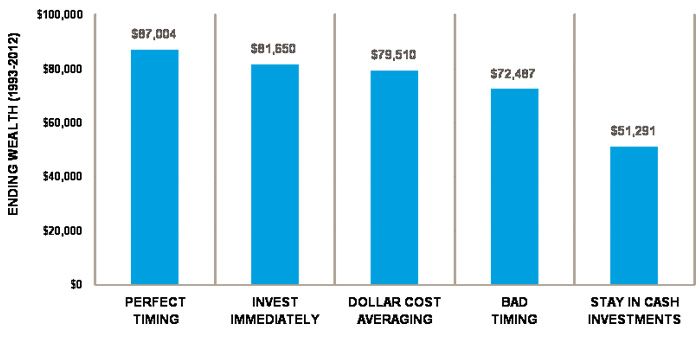

“But don’t take my word for it. Consider our research on the performance of five hypothetical long-term investors following very different investment strategies. Each received $2,000 at the beginning of every year for the 20 years ending in 2012 and left the money in the market, as represented by the S&P 500® Index.2 Check out how they fared:

- Peter Perfect was a perfect market timer. He had incredible skill (or luck) and was able to place his $2,000 into the market every year at the lowest monthly close. For example, Peter had $2,000 to invest at the start of 1993. Rather than putting it immediately into the market, he waited and invested after month-end January 1993—that year’s monthly low point for the S&P 500. At the beginning of 1994, Peter received another $2,000. He waited and invested the money after March 1994, the monthly low point for the market for that year. He continued to time his investments perfectly every year through 2012.

- Ashley Action took a simple, consistent approach: Each year, once she received her cash, she invested her $2,000 in the market at the earliest possible moment.

- Matthew Monthly divided his annual $2,000 allotment into 12 equal portions, which he invested at the beginning of each month. This strategy is known as dollar cost averaging. You may already be doing this through regular investments in your 401(k) plan or an Automatic Investment Plan (AIP), which allows you to deposit money into mutual funds on a set timetable.

- Rosie Rotten had incredibly poor timing—or perhaps terribly bad luck: She invested her $2,000 each year at the market’s peak, in stark defiance of the investing maxim to “buy low.” For example, Rosie invested her first $2,000 at the end of December 1993—that year’s monthly high point for the S&P 500. She received her second $2,000 at the beginning of 1994 and invested it at the end of August 1994, the peak for that year.

- Larry Linger left his money in cash investments (using Treasury bills as a proxy) every year and never got around to investing in stocks at all. He was always convinced that lower stock prices—and, therefore, better opportunities to invest his money—were just around the corner.

The results are in: Investing immediately paid off

For the winner, look at the graph, which shows how much hypothetical wealth each of the five investors had accumulated at the end of the 20 years (1993–2012). Actually, we looked at 68 separate 20-year periods in all, finding similar results across almost all time periods.

Naturally, the best results belonged to Peter, who waited and timed his annual investment perfectly: He accumulated $87,004. But the study’s most stunning findings concern Ashley, who came in second with $81,650—only $5,354 less than Peter Perfect. This relatively small difference is especially surprising considering that Ashley had simply put her money to work as soon as she received it each year—without any pretense of market timing.

Matthew’s dollar-cost-averaging approach delivered solid returns, earning him third place with $79,510 at the end of 20 years. That didn’t surprise us. After all, in a typical 12-month period, the market has risen 74% of the time.3 So Ashley’s pattern of investing first thing did, over time, yield lower buying prices than Matthew’s monthly discipline and, thus, higher ending wealth.”

Even bad market timing trumps inertia

The bottom line from my 10 year old: “Nobody’s perfect (in reference to Peter Perfect). I want to be Ashley (who came in second place).”

I explained to the girls that Ashley doesn’t time the markets. “OOOH, I get it now.”

Don’t time (don’t buy and hold either – the subject of whole different, hairy blog) the markets – avoid the mistakes of many investors and advisors. Instead, Get Liberated, educate yourself (and your kids) about a better choice.